Table of contents

Tax law is constantly changing, and what was true just a few years ago with the SECURE Act may not be true today with the passing of SECURE 2.0. However, there is one key factor that determines when an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) requires minimum distributions or RMDs must be taken and it plays a role in determining the best plan of action—the type of beneficiary. The RMDs will be different depending on the type of beneficiary, and the distribution strategy itself will be different depending on the tax situation of that individual. In this post, we will cover RMD rules for surviving spouses, what a non-eligible designated beneficiary is, the RMD rules that apply to them, and how each of these types of beneficiaries can optimize distributions by taking into account their tax situations.

Surviving Spouse Beneficiaries

Surviving spouse beneficiaries have the most flexible rules as it relates to Inherited IRAs. When a spouse is the beneficiary of an IRA, they have the following options:

- Assume the IRA as their own – RMDs would begin at the surviving spouse’s Required Beginning Date (RBD).

- Treat it as an Inherited IRA – subject to the 10-year rule.

- Elect to be treated as the deceased spouse – RMDs would begin at the deceased spouse’s RBD and would use the IRA Uniform Life Table of the deceased spouse instead of the surviving spouse.

As you can imagine, each one of these options provides a different lever to pull that could be more or less beneficial, depending on the goals and situation of the surviving spouse. So, how do you decide which option to choose?

Assuming the IRA As Your Own

It typically makes the most sense for a surviving spouse to assume the deceased spouse’s IRA as their own when the surviving spouse is younger than the decedent. This is especially true if the deceased spouse was already taking RMDs and the surviving spouse is not yet RMD age or has an older RMD age such as 73 or 75. In addition, the surviving spouse will be able to use their life expectancy table rather than the deceased spouse’s, making the RMDs smaller and thus preserving a greater amount of dollars in the tax-deferred vehicle.

Treating the account as an Inherited IRA

If the surviving spouse is younger than age 59.5 and needs income from the IRA for support, it would be wise to treat the account instead as an Inherited IRA to avoid incurring the 10% penalty on early distributions. If the surviving spouse is eligible to file as Qualified Widower for the two years following the death of the decedent, there is an additional tax planning possibility. During this time, the surviving spouse can benefit from Married Filing Jointly tax brackets and potentially take distributions from the IRA in a tax bracket lower than the tax rate at which the contributions were made, creating a favorable tax arbitrage.

Elect to be Treated as the Deceased Spouse

If the surviving spouse is older than the deceased spouse was, it typically makes sense to elect to be treated as the deceased spouse to delay RMDs, and/or take RMDs using the deceased spouse’s life expectancy table. See an example below:

Spouse A and Spouse B each have an IRA worth $500,000. Spouse A is age 75 and is taking RMDs, and Spouse B is age 70 and has a Required Beginning Date at age 73. Suppose Spouse B passes away and Spouse A is the sole beneficiary of Spouse B’s IRA. Spouse A has a current RMD of $20,0325 and if they were to assume Spouse B’s IRA into their own, then next year’s RMD would be around $42,000. If instead Spouse B elects to treat the IRA they inherited as if they were Spouse A, they could delay essentially $60,000+ total in required minimum distributions. If the surviving spouse was in the 22% tax bracket this would be a tax savings of about $13,000. This is a simplified example and doesn’t take into account the savings that would be generated in future years due to the arbitrage that exists between the life expectancy tables being used. In other words, RMDs for a 78-year-old are larger than those for a 73-year-old. Spouse B would be taking RMDs from the IRA they inherited as if they were five years younger than their current age, resulting in a smaller RMD than if they had assumed Spouse A’s IRA into their own.

Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries

Non-eligible designated beneficiaries (Non EDBs) are those who are named beneficiaries of an IRA but do not fall within one of the five categories to be considered an eligible designated beneficiary (EDB), which are:

- Spouses

- A child who is younger than the age of majority

- A disabled individual

- A chronically ill individual

- A person not more than 10 years younger than the deceased IRA owner

Essentially, if you’re above age 18, relatively healthy, and have inherited an IRA from someone other than a spouse, you are likely a non-eligible designated beneficiary.

After 2020, there was confusion about the new RMD rules for non-eligible designated beneficiaries of IRAs with decedents. The IRS issued guidance in Notice 2022-53 regarding this specific issue and provided relief for missed RMDs for tax years 2021 and 2022 but not 2023. If you are a non-eligible beneficiary and you inherited an IRA from someone who died after December 31, 2019, you should have taken an RMD for 2023.

The RMD rules for non-EDBs of someone who died after December 31, 2020, are:

- RMDs in year one after the death of the decedent are taken based on the life expectancy of the non-EDB.

- For the next nine years, subtract one from the original life expectancy factor to arrive at the RMD factor.

- Whatever is left at the end of the 10th year must be distributed in its entirety.

In short, the account must be exhausted within 10 years and there are yearly RMDs based on the non-EDB’s life expectancy.

Planning Possibilities for Non-EDBs

There are several ways you might consider managing your Inherited IRA if you’re a non-EDB. Suppose you have inherited from a parent an IRA worth $300,000, and you are:

- Working

- Married

- You and your spouse are age 50

Additionally, assume that you are conscious that retirement is around the corner, and you’d like to bolster your retirement savings. Currently neither you nor your spouse are maxing out your 401(k) contributions through work.

In this case you might consider distributing funds from the Inherited IRA to max out your 401(k)s. Taking money from a tax-deferred vehicle that is essentially a ticking tax bomb and funneling funds into another tax-deferred account that won’t have RMDs for about another 25 years will allow your funds to compound without tax drag for a longer period of time.

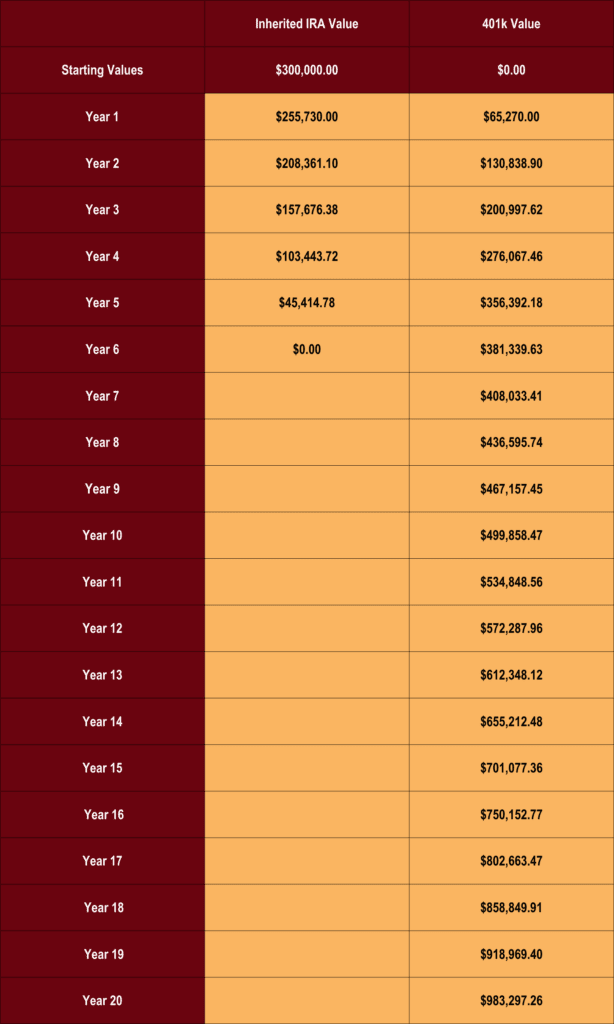

You and your spouse can each contribute $30,500 into your 401(k)s—amounting to $61,000 in total. If you withdraw $61,000 from your Inherited IRA and put $61,000 into your 401(k)s, the tax effect in that year is essentially $0 since you receive a tax deduction for every dollar you contribute to your 401(k). If you elected this route, you would exhaust your Inherited IRA in less than 10 years and contribute over $300,000 toward your retirement account, which would not incur tax until you withdrew the funds from the 401(k) in your retirement. Using this strategy, you could have almost $1 million in your 401(k) at the end of 20 years, having only contributed funds from your Inherited IRA and averaging a 7% return over that period (refer to the chart below).

On the other hand, if you were already retired, age 70.5 or older, and charitably inclined, you could elect to make Qualified Charitable Distributions, which are tax-free distributions to a public charity made directly from your IRA. This would help fulfill your RMD without incurring any tax and simultaneously achieve your charitable giving goals.

If instead you took your RMD, deposited it in your bank account and then gifted it to your charity, it would incur unnecessary taxes. For example, if the distribution was $10,000 and you were in the 22% marginal tax bracket, you would have paid $2,200 in taxes!

Bottom Line

The SECURE 2.0 Act changes are here, and they’re significant for anyone with an inherited IRA—spouses and non-eligible designated beneficiaries alike. The main takeaway is simple: if you inherit an IRA, know your beneficiary category and how it affects your RMDs. For spouses, the flexibility is unprecedented; they’ve got a real opportunity to optimize based on their financial situation. Non-eligible beneficiaries are on a tighter leash with the 10-year rule, but that doesn’t mean they’re out of options.

Here’s the bottom line: Understanding these rules is important but using them to your advantage is where the real work begins. Whether it’s deciding how to treat an inherited IRA as a spouse or figuring out how to manage distributions as a non-eligible beneficiary, the strategy you choose needs to reflect your financial goals and tax situation.

Inheriting an IRA can provide a financial windfall, but it also comes with complex rules and potential tax implications. Understanding your options for managing an inherited IRA is essential to minimizing taxes and preserving your inheritance. For Arizona retirees navigating inherited IRAs or other financial decisions, our free Arizona Retiree Toolkit offers tailored advice to help you manage your inheritance wisely and plan for the future. Download your copy here and take control of your retirement planning today.

It’s time to get moving. What’s your plan?