Table of contents

Several financial concepts can be simplified to the familiar lemonade stand. Compound interest is no different. It’s an elementary level concept where the earnings that your investments create then start creating their own earnings. To use the lemonade stand analogy, you use your profits from the lemonade stand and open a new lemonade stand, which then creates more profits. The same is true as it relates to traditional investments like mutual funds and stocks. The concept of compound interest is simple, but truly understanding it can be quite complex.

Why is it so hard to comprehend?

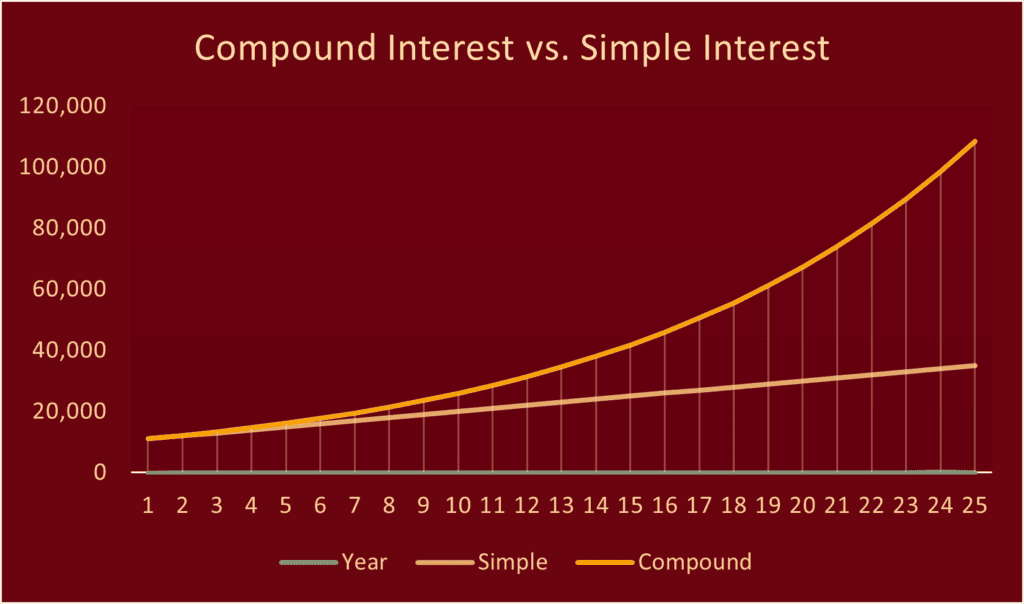

The elementary illustration of a lemonade stand is very easy to comprehend. As you start to expand, the results of compound interest over time are eye-opening.

The reason compound interest can be challenging to understand is that it works exponentially, not linearly, as simple interest does. For example, if you had $10,000 that earned 10% at the end of one year, you would have $11,000. If you were thinking linearly, at the end of two years you would have $12,000. However, compound interest works such that your interest is earning interest, so instead of having $12,000 when your interest is compounding, you end up with $12,100. Not a dramatic difference in a short period of time. However, when you draw this out over 25 years, the results are astounding. If you compare compound interest to simple interest over a 25-year period of time, still using a growth rate of 10%, you end up with $35,000 for simple interest and $108,347 for compound interest.

You can now see why some have called it the eighth wonder of the world.

How it can work for you

Rule of 72

One common rule of thumb you can use is called the Rule of 72. The way the Rule of 72 works is by taking the annual rate of return of an investment and dividing that by 72 to arrive at the approximate time period it takes to double. As an example, if you had a $10,000 investment that got a 9% annual return, you would take 72÷9 and arrive at roughly 8 years, at which point your money would double to $20,000. Again, if you expand this to the next eight years, you would have about $40,000, then another eight years: $80,000, and another eight years: about $160,000. So, 32 years after your $10,000 investment, you would have about $160,000.

The key component of that example is time, 32 years. I would make the very strong argument that you should focus far more on time IN the market than timing the market.

Volatility: The Accumulator’s Friend

Financial media tends to shriek every time the markets have significant declines. As a goal-focused, planning-driven investor, you should be doing a happy dance when markets are volatile. Volatility can often times be misconstrued simply as declines in the market. However, volatility includes both short spikes up and short spikes down in the markets. For someone with recurring contributions into their investment accounts, this automatically creates a tool that buys more when prices are low and less when prices are high. It is certainly worth noting that this is exactly the opposite of what financial media will steer you towards. When prices are high, you end up buying less shares while investing the same dollar amount; when prices are low, you end up buying more shares with the same dollar amount. Simply sticking to this strategy allows an individual investor to outperform the underlying fund itself when markets are volatile. Warren Buffett once said, when speaking at a Berkshire Hathaway meeting, “We would make more money if volatility [were] higher because it would create more mistakes. Volatility is a huge plus to real investors.”

How it can work against you

If you are a borrower as opposed to an investor, then you are the one who pays the investor. As an example, most home mortgages are repackaged and sold to investors in the form of bond funds. The interest payment each month on the bond is received in the form of an interest payment to the investor. Some debts like credit cards and student loans are compounding debts, where the interest accumulation compounds on top of the principal amount.

The student loan crisis can be easy to comprehend when viewed through this lens. Imagine you had a $20,000 student loan at 6% interest. When you graduated college, you elected to defer your payments. Using the Rule of 72, you know that the student loan balance is going to double roughly every 12 years. Imagine that you made no payments until your mid 40s, then woke up and saw you had an $80,000 student loan balance. You might think to yourself, “I’m pretty sure that balance was around $20,000,” and you’d be correct. The additional $60,000 is the interest compounding on top of itself. Credit cards work in a very similar manner with the interest rates typically being higher.

As illustrated, compound interest can be a large windfall if used to your advantage. If you are the victim to compound interest, it can slowly erode your plan. Make sure your plan is putting compound interest to work in your favor. If you need help putting a plan together, please reach out.